The Extraordinary Life of John Craske

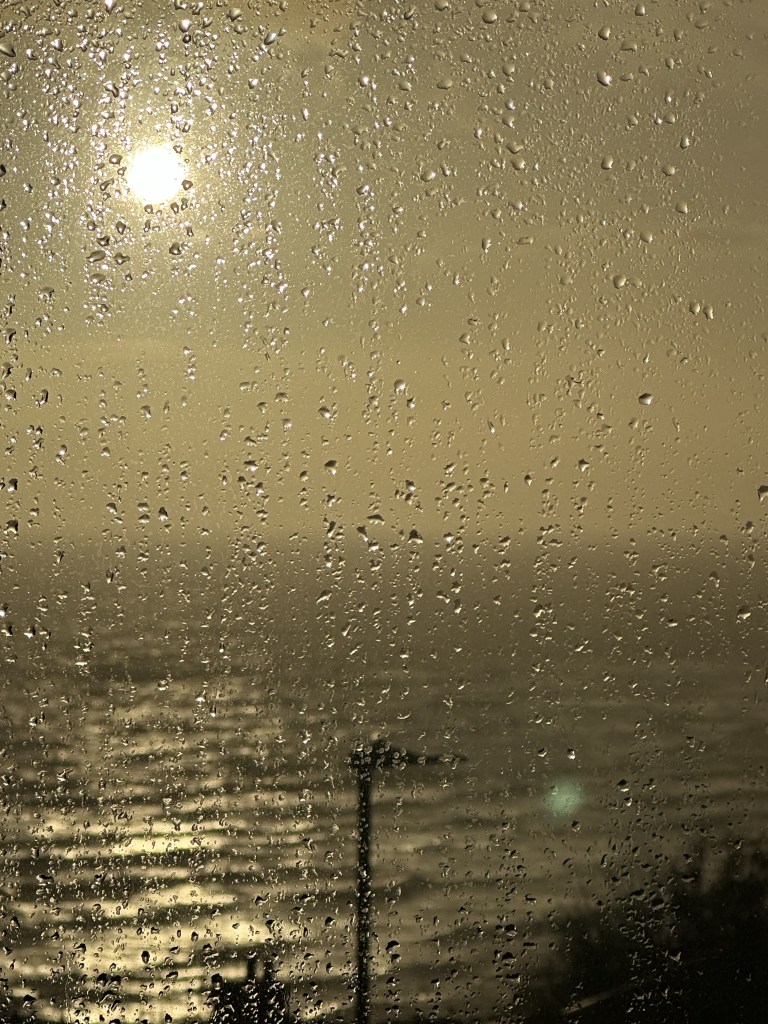

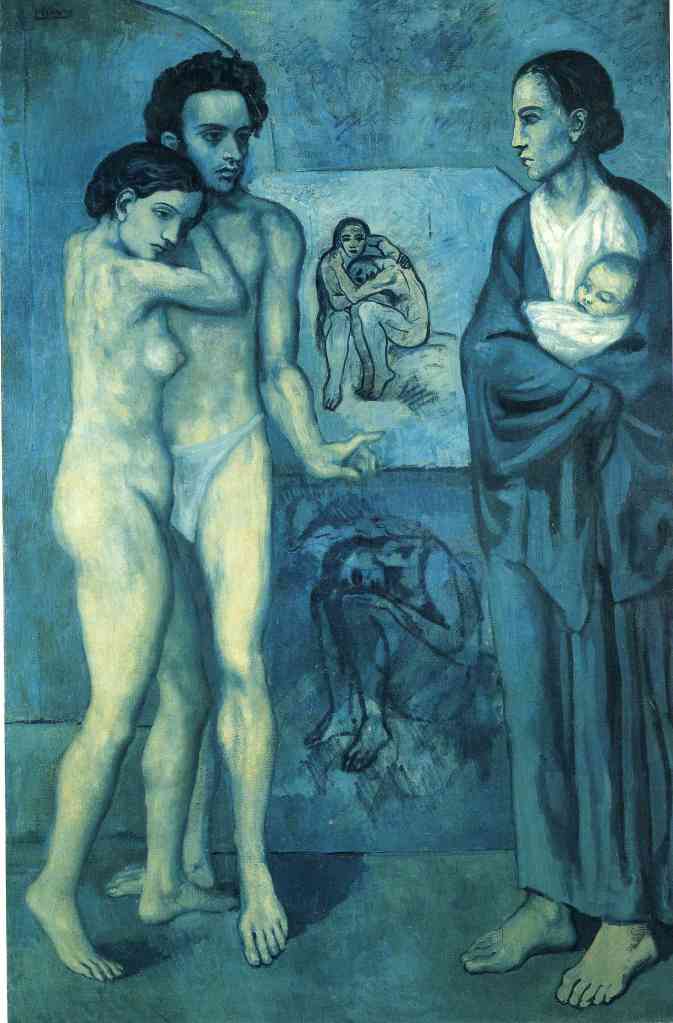

As he fell in and out of conscious, John dreamt of the sea, he remembered his life on the Sheringham fishing boats, the hard lads with their salty language and humour, the sheer pleasure of the wind and rain against his face, it was the best life he had ever had and the only time that life was worth living. These times were now over and, maybe, he felt his own life was also over. But he kept a kernel of hope, deep in his unconscious, and that seed flowered and became a means of survival, a solace and a thing of beauty.

I have been visiting Sheringham on a regular basis for more years than I care to remember, from the time my parents moved to the area in the 1990s. But, much to my shame, it is only recently that the name John Craske has come to my notice. But since then, I have learnt more and more about this fisherman, who turned to art in tragic circumstances, as a means of recovery and survival, producing marvellous pictures of the sea, both in watercolours and then embroideries, when his already fragile health began failing him.

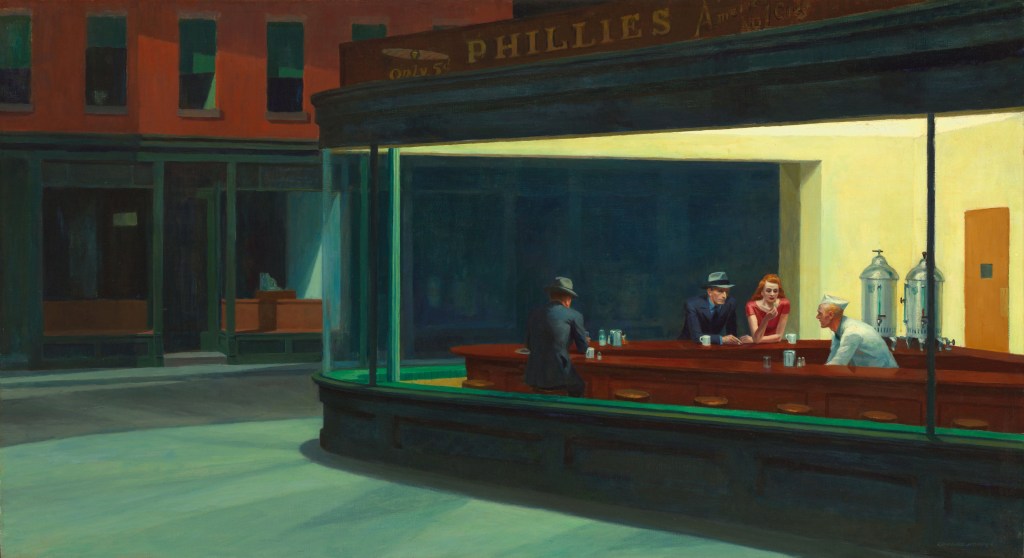

Sometimes people are born in the wrong place at the wrong time. In 1928, renowned artists Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood walked past a small fisherman’s cottage in St. Ives, and spied a retired fisherman Alfred Wallace painting seascapes by the hundreds, to escape his loneliness, following the death of his wife. Wallace became well known through his association with the St. Ives artists and his work is now famous throughout the world. Replace Alfred Wallace with John Craske and the story might have been totally different.

As a result, the work of John Craske is almost unknown and it is only in more recent years that his star has started to rise, following the publication of ‘Threads’ by Julia Blackburn, a beautiful book restoring Craske’s reputation as a truly underrated ‘Outsider’ artist, whose work should be more widely known and appreciated.

John Craske was born in Sheringham in 1881 from an established fishing family in the town. The Craske family had been fishermen in Sheringham for as many generations as people could remember, it’s what they did. By the time he was 14, John was out on the boats in all weathers, facing the might of the North Sea, a deep sea fisherman.

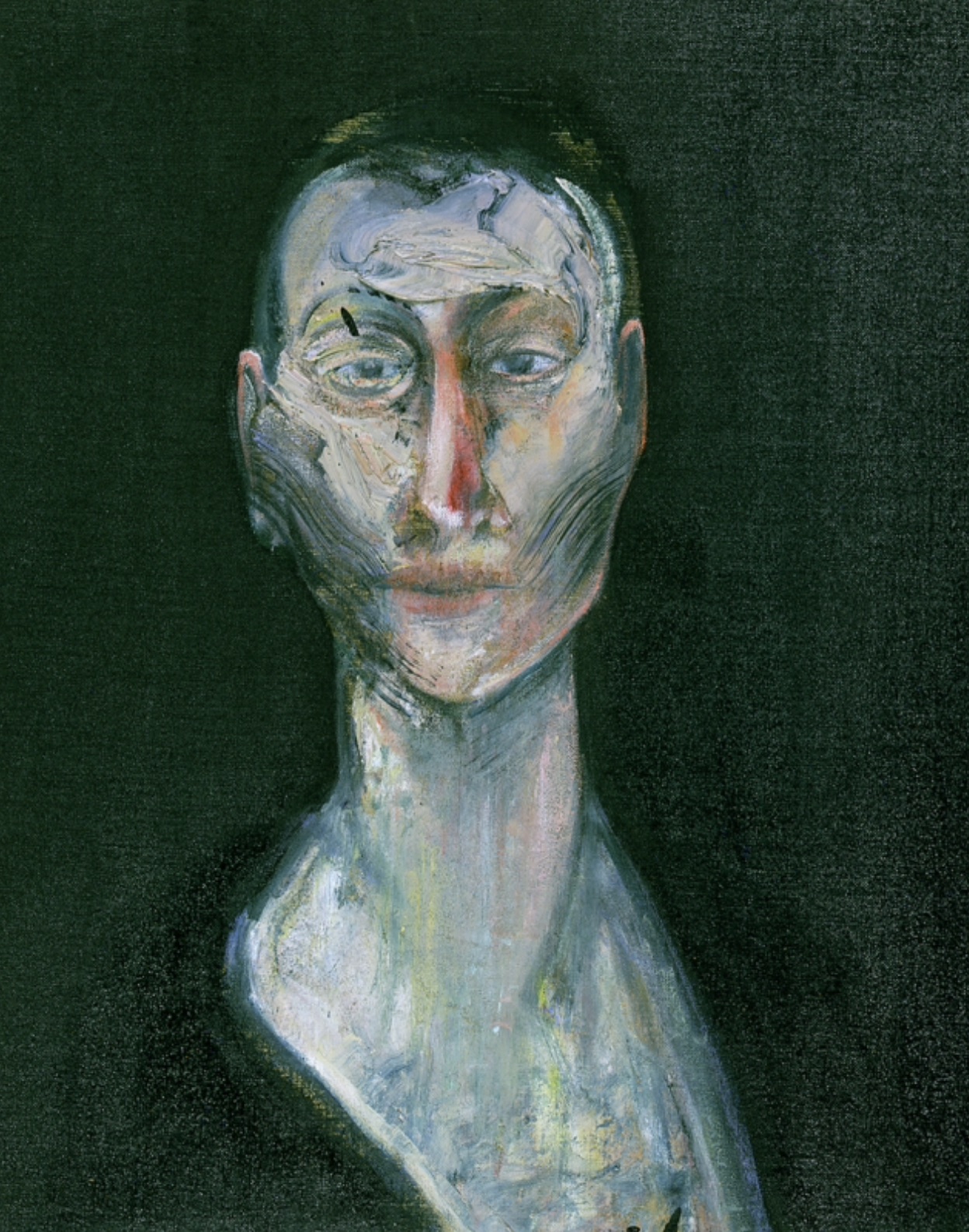

This early picture of John, shows a rather sensitive young man, perhaps not cut out to be a fisherman.

The Norfolk singer Harry Cox was born in 1881, the same year as John Craske and this old Norfolk folk song ‘Windy Old Weather’ recorded by the Folklorist Alan Lomax, gives you a feel of what it was like working on the fishing boats, in all weathers. John may well have heard, and even sang, this popular Norfolk song, while on board one of these trawlers.

“It was stormy old weather, windy old weather,

When the wind blows, we all pull together.”

At the beginning of the 20th century, times were becoming increasingly tough for the Sheringham fishermen, due to the increase in tourism in the town, and for a few years the Craske family moved up to Grimsby, where the fishing was better. However, in 1905, the Craskes did the unthinkable, they bowed to the inevitable and moved inland to Dereham, where they became fishmongers, eventually opening a shop in Dereham.

In Dereham, John met Laura, his life companion, and after they were married, John ran a business travelling round Norfolk, selling fresh fish to the local community, from his pony. He worked long hours, to make ends meet and his health started to suffer, as he had always been somewhat frail.

It is ironic that according to sources, the surname Craske, which is of pure East Anglian origin, supposedly derives from the Latin “Crassus”, meaning “one who is hale & hearty, in good health and spirits”. That description certainly did not apply to poor John Craske.

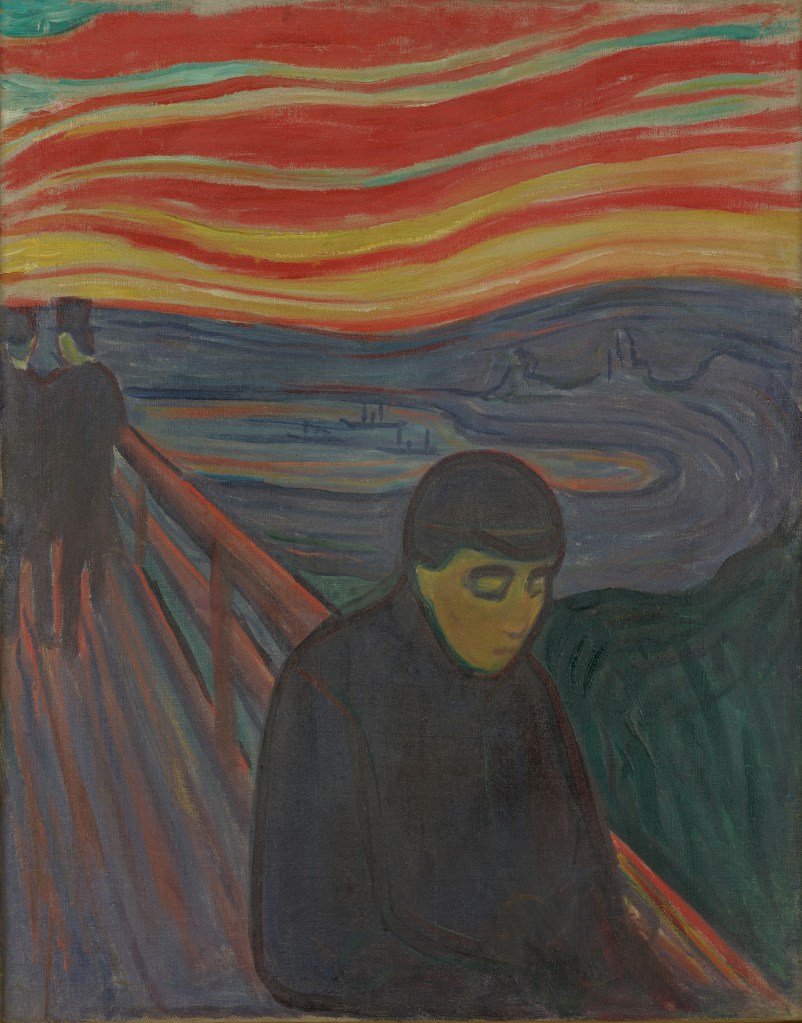

However, it was the First World War that did for him. Towards the end of the war he was ‘passed fit to fight’, but within a short time he contracted influenza, which resulted in a state of collapse from which he never properly recovered. During this first period of total stupor and insensibility, he was sent to an asylum in Norwich, but eventually it was felt he could be discharged and be cared for by his family. He was initially diagnosed with a brain abscess, but with no real evidence to back this up.

But what was he actually suffering from? According to accounts, he had long periods of total insensibility where he lay in a ‘stupor’, semi conscious and unable to speak, from which he would then awake to a type of semi-normality. There have been all kinds of theories from a type of brain tumour or the effects of diabetes, which he did indeed suffer from later in life.

There is no doubt, however, that he suffered various symptoms for the rest of his life and had to be constantly nursed and protected from the world by his devoted wife Laura. In the aftermath of the Covid epidemic, some of the symptoms appear strikingly similar to some forms of Long Covid, together with the connection between his bout of influenza and his subsequent debilitating tiredness and weakness, which also show similarities to serious recorded cases of ME/CFS (Myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome).

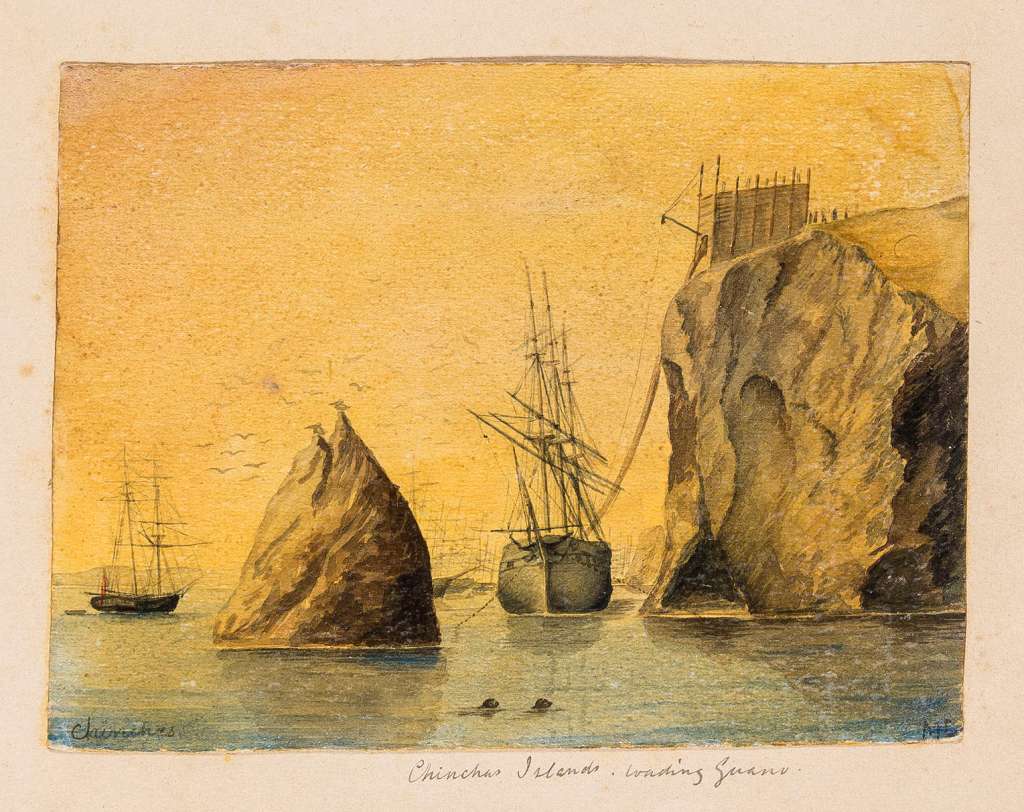

Following the death of his Dad in 1920, John had a further relapse and was mostly confined to a wheelchair. Laura decided to improve his spirits by moving to coast at Blakeney for several months, where they borrowed a small boat from a friend and they went sailing together in the relatively calm waters of the Blakeney estuary. This greatly improved his health and when he returned home, Laura bought him some paint and encouraged him to start making pictures, to remind him of the sea.

Again, over the next few years, his health deteriorated again and, in 1929, when he became confined to his bed for long periods of time, he started sewing using a frame made up from an old deckchair. This was the start of a new stage in his life as an artist.

John Craske might have disappeared into total obscurity, only known by his immediate family, but for a chance encounter with a well known poet, Valentine Ackland who visited him at the end of the 1920s after buying a model boat made by him. She became entranced by his paintings. And introduced the Craskes to her lover, the well known novelist Sylvia Townsend Warner, who opened many doors for John Craske, leading to a number of exhibitions in London and New York. Later in her life Warner donated a number of paintings to her friend, the singer Peter Pears, who greatly admired the works and they are now in the hands of the Britten Pears Foundation at the Red House Museum in Aldeburgh.

This brief period of fame did not last long and the life and work of John Craske once again faded into relative obscurity, until a new generation of admirers, including Julia Blackburn, in her biography, Threads, began raising the profile of this fisherman artist, in the 21st century.

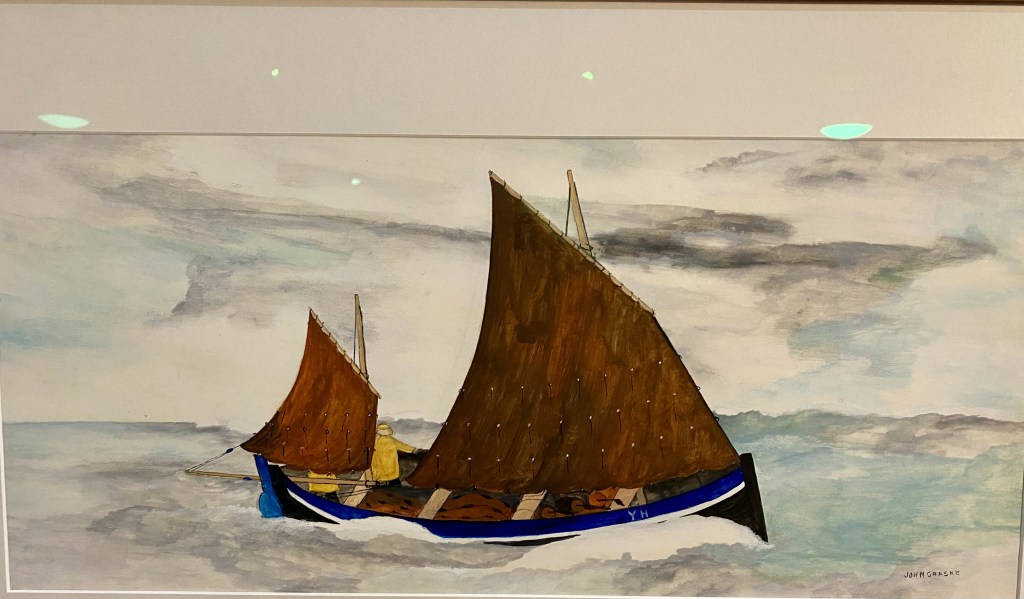

On a recent trip to Sheringham, I was determined to make up for all those years of ignoring John Craske and I wanted to see as many Craske artworks as I could. My first stop was Sheringham Museum. I was not disappointed, on the first floor there is a corner dedicated to John Craske, with many of his early watercolours and a number of his embroideries, most of which have been donated by his relatives.

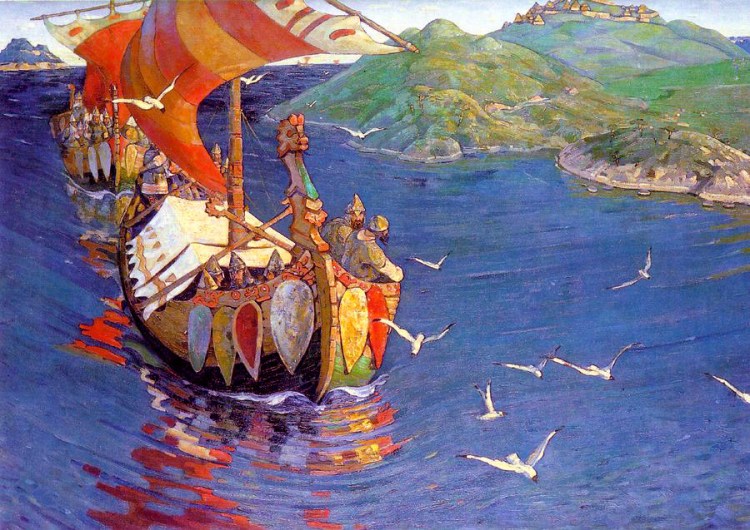

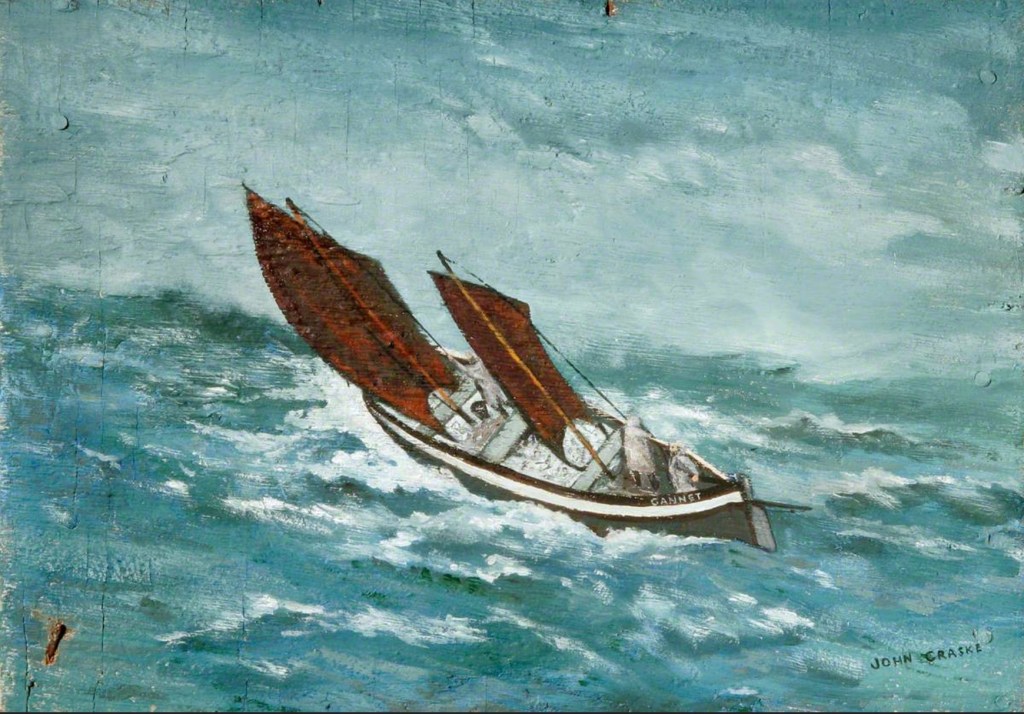

Looking at all this material in one place is very enlightening, the early sea paintings, in a limited colour palette, are very moving and give an incredible feel of how it feels to be out in rough seas, with the pitching and tossing of the waves. It is difficult to believe that Craske was a totally self taught artist, together the extraordinary fact that these paintings are based purely on his memories of being at sea.

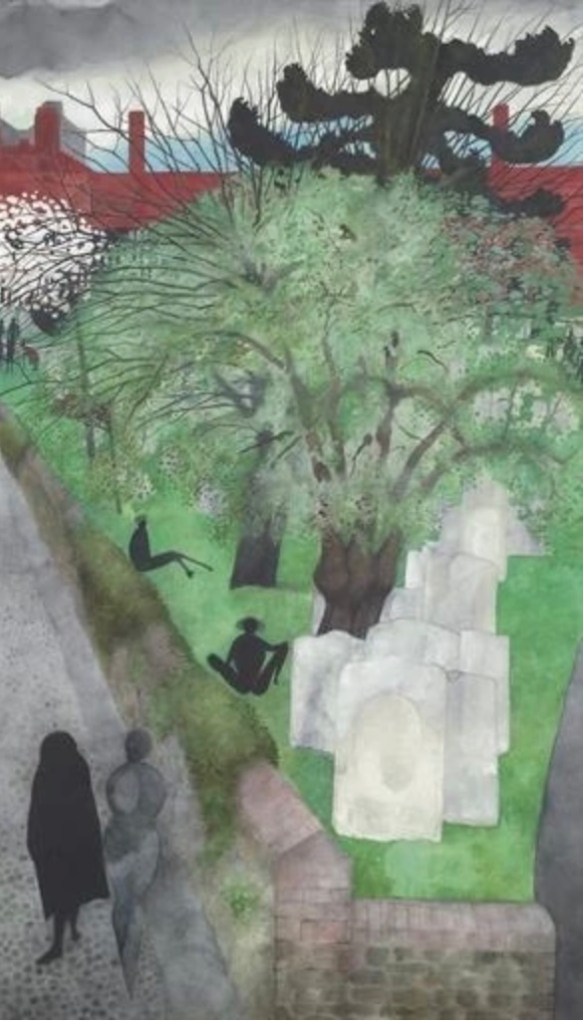

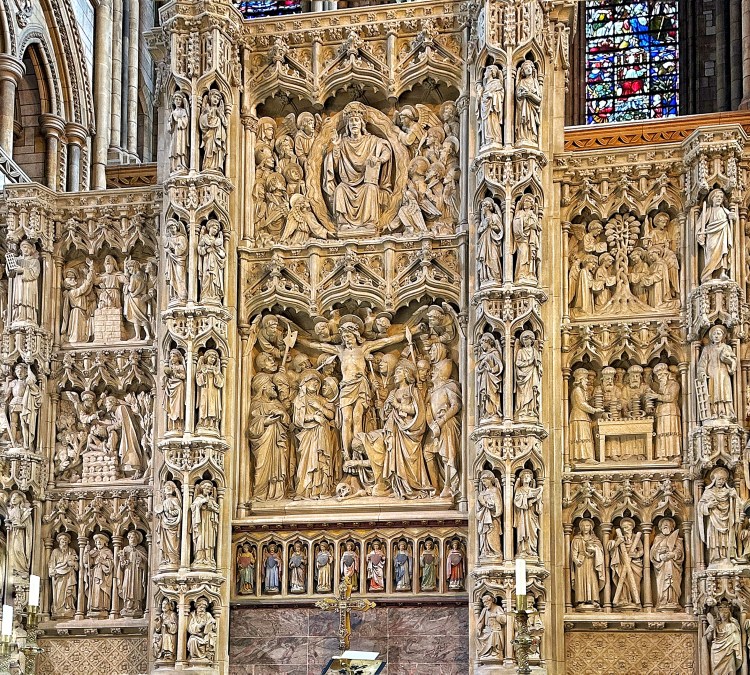

There are also the embroideries, which are totally unique. There is a long tradition of sewing by Fishermen, after all they made and repaired the nets that they used to ply their trade. And there is also a tradition of embroideries by fishermen, normally of boats, which generally fall into the category of folk art. But John Craske’s work is on a totally different level. The work below is called ‘Smile at the Storm’ showing a lighthouse and a lifeboat rescuing a sailor in stormy seas. Craske creates an incredible feel for the rough seas, by his use of stitching, building up the waves to create almost a 3D image.

His wife Laura wrote about this embroidery:-

“That picture is hanging in the front room. It is a tempest at sea and there is lightening in the sky, and a wreck, and a lifeboat with one man saved. And John put on it ‘With Christ in the vessel we’ll smile at the storm’. I never look at that picture but that I live that scene over again”

I was also greatly taken by ‘Basket of Fish’ an allegorical picture showing the reliance on fishing for the survival of the coastal community.

There are also a couple of Craskes on display at the the Glandford Shell Museum near Blakeney. The Shell museum is unlike any other museum, you’ll ever find. Housed in a lovely old Norfolk building, it has, as you would expect shells by the thousand, but also many other items of interest, including fossils, archeological finds and much more, a true museum of curiosities. And, of course there are the Craskes. There is a lovely watercolour of a schooner listing in heavy seas, and a stunning panoramic embroidery of the coast, bringing to life, from John’s memory, the time that he had spent sailing there after his illness. A true Tour De Force.

Even more extraordinary, was an embroidery which Craske was working on towards the end of his life between 1940 and 1943 depicting the retreat at Dunkirk. This monumental work, a modern day Bayeux tapestry, based purely on radio reports and photographs, shows a world of mayhem and terror as men queued up on the beaches to be rescued. Craske had moved from depictions of life at sea into a mythic realm and had become a storyteller in wool. This work was unfinished when he died and is now in the possession of Norwich Museum.

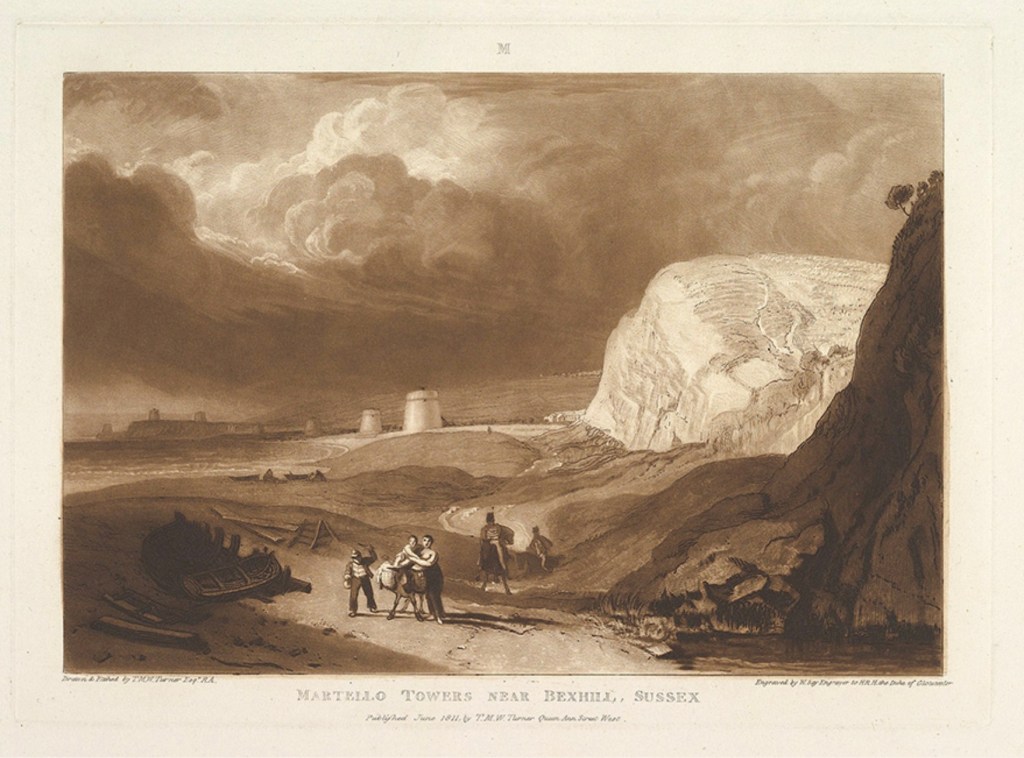

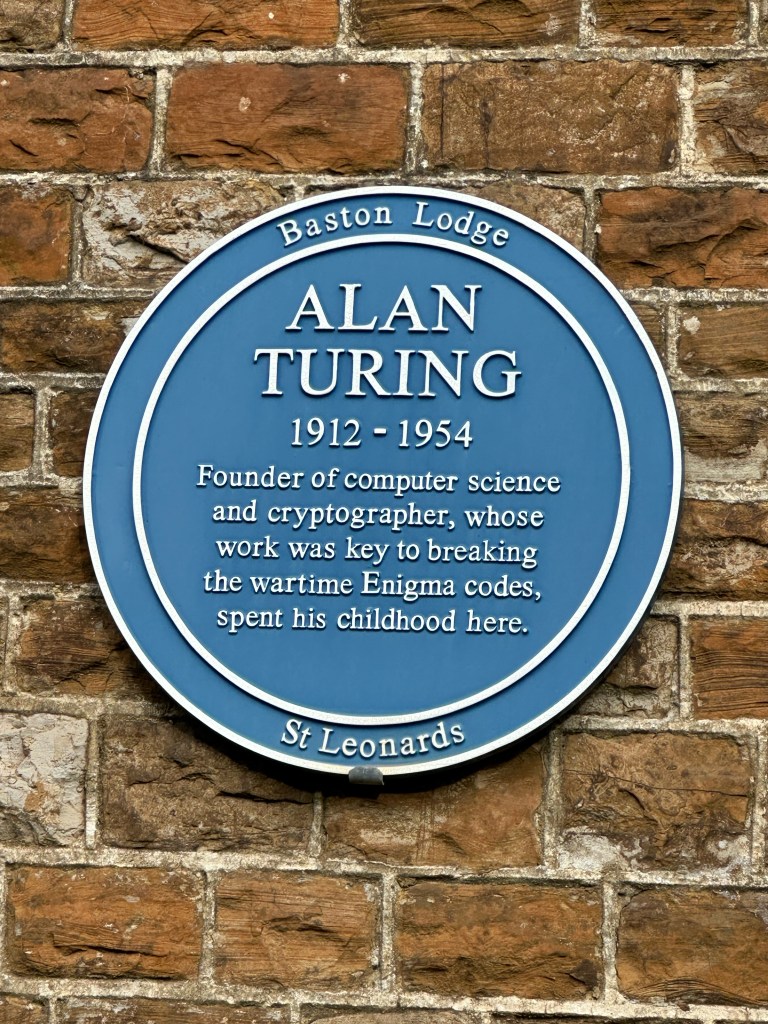

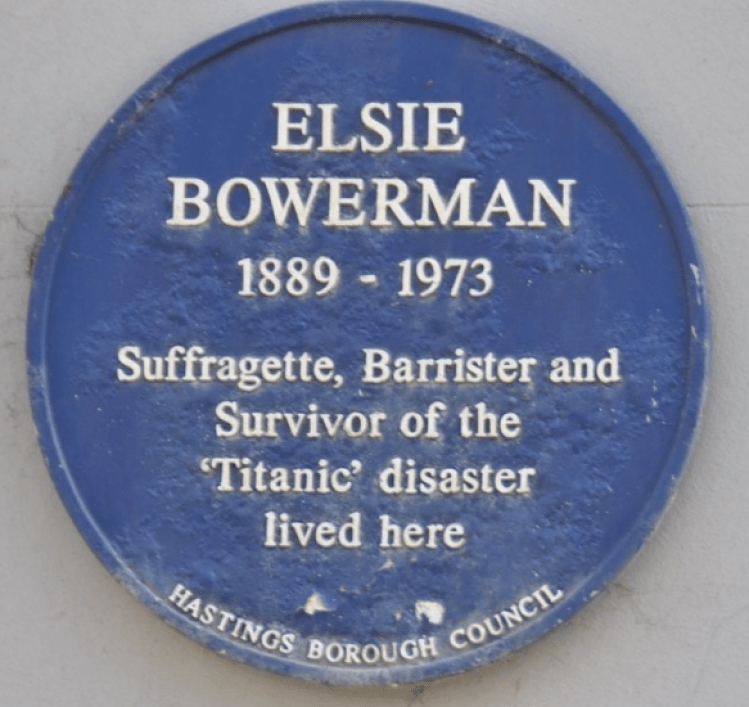

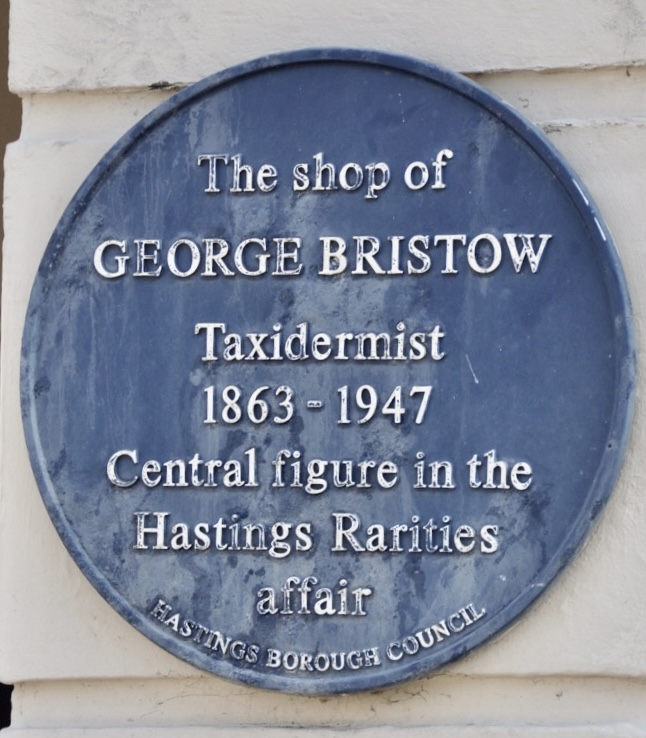

On my last evening in Sheringham, I walked down to the seafront and looked at the handful of fishing boats that remain, a sad reminder of a once thriving industry with over 200 boats. I compared it to my home town of Hastings, which still has a thriving fishing fleet, home to the largest beach-launched fishing fleet in Europe and meditated on how fortunes rise and fall.

I tried to imagine Sheringham at the turn of the 20th century, the world in which John Craske lived, full of tough, hardy and rugged men. Although, he loved the sea as much as life itself, John was perhaps too delicate a soul for the things that life threw at him and he spent the rest of his life, living inside his head, reliving his time at sea through paint and embroidery. But he was also nothing, without the love and support of Laura, who nursed him uncomplainingly during every downturn.

Painting and Embroidering was an existential need for John Craske, giving him a meaning for his frail life. His heroic life needs to be recognised, not just in East Anglia, but in the wider artistic community, a true original and worthy companion to that other great fisherman artist, Alfred Wallace.